The Principal Germanic GodsJakob Grimm |

HEIMDALL: THE GUARDIAN OF THE HEAVENLY BRIDGE Besides

the gods dealt with above who can be proved beyond any doubt as worshipped

by all or most German tribes, the Norse mythology includes a succession

of others whose traces are either more difficult follow or have completely

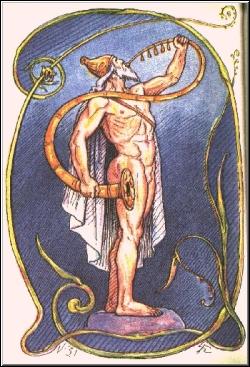

vanished. Heimdall is, like Baldur, a kindly god of light, guarding the

rainbow bridge to heaven (Bifrost) and living in Himinbjörg, the mountain

of heaven. Other features are almost fabulous: he is said to have been

the son of nine mothers, to need less sleep than a bird, to see a hundred

miles into the distance by night as by day, and to hear the trees growing

on the earth, the wool on the back of a sheep. [Image: Heimdall, watchman

of the gods.] Besides

the gods dealt with above who can be proved beyond any doubt as worshipped

by all or most German tribes, the Norse mythology includes a succession

of others whose traces are either more difficult follow or have completely

vanished. Heimdall is, like Baldur, a kindly god of light, guarding the

rainbow bridge to heaven (Bifrost) and living in Himinbjörg, the mountain

of heaven. Other features are almost fabulous: he is said to have been

the son of nine mothers, to need less sleep than a bird, to see a hundred

miles into the distance by night as by day, and to hear the trees growing

on the earth, the wool on the back of a sheep. [Image: Heimdall, watchman

of the gods.]

His horse is called Gulltoppr ("golden crop") and he himself has golden teeth. As sentinel and keeper of the gods Heimdall blows a loud horn (Gjallarhorn) which is kept under a sacred tree. He seems to have ruled during the creation of the world and of men and to have played a higher role than was afterwards allotted to him. Just as war was superintended by Ziu along with Wodan, fertility by Frô, so may creative power also have been shared between Odin and Heimdall. A song of suggestive design in the Edda [viz. Rigsthula] makes the first arrangement of mankind in classes proceed from the same Heimdall, who traverses the world under the name of Rig. LOKI: THE INSTIGATOR OF MISFORTUNE AND THE GOD OF FIRE The three brothers Hlêr, Logi, Kari on the whole seem to represent

water, fire and air as elements. Now a striking narrative in the Prose

Edda places Logi ["flame, fire"] by the side of Loki, a being from

the giant province beside a kinsman and companion of the gods. This is

no mere play upon words; the two really signify the same thing from different

points of view, Logi the natural force of fire, and Loki, with a shifting

of the sound, a shifting of the sense. From the burly fire-giant Logi has

developed a crafty, seductive evil-doer. Both can be compared to the Greek

Prometheus and Hephaestus.

The three brothers Hlêr, Logi, Kari on the whole seem to represent

water, fire and air as elements. Now a striking narrative in the Prose

Edda places Logi ["flame, fire"] by the side of Loki, a being from

the giant province beside a kinsman and companion of the gods. This is

no mere play upon words; the two really signify the same thing from different

points of view, Logi the natural force of fire, and Loki, with a shifting

of the sound, a shifting of the sense. From the burly fire-giant Logi has

developed a crafty, seductive evil-doer. Both can be compared to the Greek

Prometheus and Hephaestus.

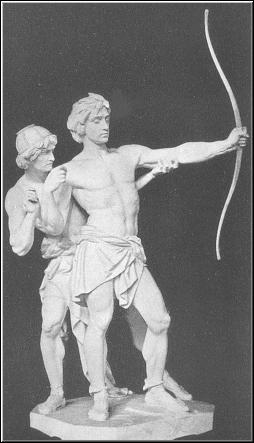

Loki, as punishment for his misdeeds, is laid in chains, like Prometheus who gave men fire, and from which he will be freed at the end of the world. One of Loki's children, Fenrir, pursues the moon in wolf's shape and threatens to swallow it. Eclipses of sun and moon were terrifying to many pagan peoples. The gradual darkening over of the glittering sphere seemed to be that moment of time when the yawning gullet of the wolf threatened to swallow the moon and they believed that aid was given to the latter by uttering loud cries. [Image: "Loki and Hod" by C. Qvarnstrom (c. 1890). Loki tricks the blind god Hod into killing Baldur with a dart of mistletoe.] This breaking loose of the wolf

and the future release of Loki from his bonds, who at the time of Ragnarok

will fight and overcome the gods, coincides strikingly with the release

of Prometheus by whom Zeus is to be overthrown. Prometheus is chained to

rocks by Hephaestus, like Loki in similar manner by Logi, son of the giant

Fornjotr.

Loki was beautiful in appearance but evil of mind. His father, a giant, was called Farbauti, his mother's names were Laufey and Nal, slim and supple. By his wife, Sigyn, Loki had Nari or Narvi, and three children with a giantess, Angrbotha: the wolf Fenrir, the serpent Jormungandr and Hel, a daughter with whose name the personal concept vanished and was dissolved in the local idea of Hellia, underworld and place of punishment. Loki is said to be the terminator and destroyer of all things, in contrast to Heimdall, the beginner and originator. FRIGGA AND FREYAGermanic goddesses, travelling around and visiting houses, are chiefly thought of as mothers of the gods from whom the human race learned the affairs and arts of the household as well as of farming: spinning, weaving, sowing and harvesting. These labors bring peace and calm into the land and the memory of this persists in delightful traditions even more firmly than in wars and battles, which most goddesses, like women generally, avoid. But as some goddesses also take kindly to war, so do gods on the other hand favor peace and agriculture; and there arises an interchange of names or offices between the sexes.Among the goddesses of the Norse religous system, of whom unequivocal traces are forthcoming in the rest of Teutondom, we first encounter Frigga, Odin's wife, and Freya, sister of the god Freyr, a pair easy to confound and often confounded because of the their similar names. The forms and even the meanings of the two names border closely on one another. Freya means the gay, joyful, dear, gracious goddess. Frigga, Wodan's wife, signifies the free, beautiful and amiable one. With the former is connected the general concept of Frau (woman, lady), with the latter that of fri (wife, mistress). Frigga, as wife of the highest god, has rank before all other goddesses. She knows the destinies of men, is consulted by Odin, administers oaths; she superintends marriages and is entreated by the childless. In some parts of northern England, in Yorkshire, especially Hallamshire, popular customs show remnants of the worship of Frigga. In the neighbourhood of Dent, at certain seasons of the year, especially autumn, the country folk hold a procession and perform old dances, one called the giant's dance: the leading giant they name Woden, and his wife Frigga, the principal action of the play consisting in two swords being swung and clashed together about the neck of a boy without hurting him. The distinct trace of the goddess in lower Saxony is worth noting where she is called Fru Freke by the people and appears in the roles which we allot to Frau Holle. Then in Westphalia, legend may derive the name of the old convent Freckenhorst, Frickenhorst, from a shepherd Frickio, to whom a light appeared in the night on the spot where the church was to be built; the name really points to a sacred hurst or grove of Frecka fem., or of Fricko masc., whose site Christianty was perhaps eager to appropriate. A constellation of the heavens, Orion's belt, is called Fraggiar rockr after the highest goddess. But the constellation also means Mariarock, Marirock in Danish because Christians applied the old name to Mary the heavenly mother. Freya, from whose name comes the sixth day of the week, is after, or alongside Frigga the most honored goddess, indeed her cult seems to have been even more widespread and important. She was married to a man called Odr, not a god, at least not included among the Aesir, but who forsook her and whom she, shedding tears, sought all over the world among alien peoples. Freya's tears were golden, gold is called after them, she herself is gratfagr, beautiful in weeping. In children's tales, pearls and flowers are shed with tears or laughter. But according to the oldest evidence, Freya appears warlike. She drives to the battlefield on a wagon drawn by two cats, just as Thor drives with two goats, and she shares with Odin in the slain. She is called supreme head of all Valkyries. As a consequence it seems a remarkable similarity that in legend from Christian times, besides Wodan, Holda or Berchta also take up unbaptized, dying children into their host, i.e., as pagan goddesses they take the souls of pagans.

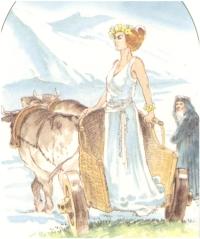

Freya in her cat-drawn chariot; N.J.O. Blummer (1852). Freya's dwelling is called Folkvangr, Folkwang, the fields on which hosts of the (dead?) folk gather. This possibly resembles St. Gertrud, whose minne is drunk for the souls of the departed; with Gertrud the souls of the dead are given hospitality the first night. Freya's hall is called Sessrymir, roomy in seats, taking up hosts of people. Dying women believe they come into her company after death. Thorgerd in Egils saga refuses earthly nourishment; she thinks to feast with Freya soon in the afterlife: "I have not had supper, and I will have none till I am with Freya". Yet love-songs please her too, and lovers do well to call upon her. Because the cat is sacred to her, as the wolf to Wodan, perhaps explains to us why this animal is regarded as the associate of night-hags and witches and is called Donneraas, Wetteraas (thunder carrion). If a bride goes to her wedding in good weather, then it is remarked: "She has fed the cat well," i.e. not offended the animal of the goddess of love. According to the Edda, Freya owned a precious necklace. How she obtained the jewel from dwarfs, how it was cunningly robbed from her by Loki, is recorded in an original tale. When Freya snorts in rage, the necklace breaks off at her breast. When Thor, to get his hammer back, dresses up in Freya's garments, he does not forget to put on her famous necklace, Brisinga men ["necklace of the Brisings.] Now this very trinket is evidently known to the Anglo-Saxon poet of Beowulf (line 1199); he names it Brosinga mene ["necklace of the Brosings"], without any allusion to the goddess. I would read "Brîsinga mene," and derive the word in general from a verb which is in MHG brîsen, breis (nodare, nodis constringere, Gr. kentein to pierce), namely, it was a chain strung together of bored links. The jewel is so closely interwoven with the myth of Freya, that from its mention in Anglo-Saxon poetry we may safely infer the familiarity of the Saxon race with the story itself. NERTHUS: MOTHER EARTH In

almost all tongues earth is female in gender and, in contrast to the father

sky surrounding her, regarded as the mother who gives birth, who brings

forth fruits. Nowhere is her maternal quality expressed purer and simpler

than in the oldest information which we possess in the

Germania

of Tacitus about the goddess Nerthus. Writes Tacitus: "The German peoples

as a whole honor Nerthus, who is Mother Earth, and believe that she mixes

in human affairs and comes journeying in a wagon among her people. On an

island in the sea lies an inviolate wood sacred to her; her wagon stands

there, veiled with a cloth, and only a single priest may approach it. The

latter knows when the goddess appears in the wagon. Two she-oxen pull it

away and the priest devoutly follows. Wherever she condescends to come

and accept hospitality, there are days of rejoicing and weddings, no war

is fought, no weapon reached for, every iron object is locked away. Only

peace and calm are then known and desired. This lasts until the goddess

has sojourned long enough among humans and the priest leads her back again

into her sanctuary. Cover and goddess are washed in a remote lake. But

the servants who perform are afterwards swallowed by the lake. A secret

terror and sacred uncertainty are therefore always spread over this, which

only those who die immediately afterwards witness." [Image: Earth Mother

Nerthus on her chariot/wagon.] In

almost all tongues earth is female in gender and, in contrast to the father

sky surrounding her, regarded as the mother who gives birth, who brings

forth fruits. Nowhere is her maternal quality expressed purer and simpler

than in the oldest information which we possess in the

Germania

of Tacitus about the goddess Nerthus. Writes Tacitus: "The German peoples

as a whole honor Nerthus, who is Mother Earth, and believe that she mixes

in human affairs and comes journeying in a wagon among her people. On an

island in the sea lies an inviolate wood sacred to her; her wagon stands

there, veiled with a cloth, and only a single priest may approach it. The

latter knows when the goddess appears in the wagon. Two she-oxen pull it

away and the priest devoutly follows. Wherever she condescends to come

and accept hospitality, there are days of rejoicing and weddings, no war

is fought, no weapon reached for, every iron object is locked away. Only

peace and calm are then known and desired. This lasts until the goddess

has sojourned long enough among humans and the priest leads her back again

into her sanctuary. Cover and goddess are washed in a remote lake. But

the servants who perform are afterwards swallowed by the lake. A secret

terror and sacred uncertainty are therefore always spread over this, which

only those who die immediately afterwards witness." [Image: Earth Mother

Nerthus on her chariot/wagon.]

This beautiful tale of Mother Earth agrees with what is contained in reports about the cult of a deity to whom peace and fertility were attributed. In Sweden it was Freyr, son of Njord, whose curtained car passed through the land in Spring, with the people all praying and holding feasts. The alternation of male and female deities sheds a welcome light here on why spells and rhymes used with Wodan as harvest god are actually transferred in other Lower German districts to a goddess. When the cottagers, we are told, are mowing rye, they leave a few stalks standing, tie flowers among them, and when they have finished work, assemble around the clump left standing, grasp the ears of rye, and shout three times over: Lady Gaue, keep your fodder

Whereas Wodan had better fodder promised him for the next year, here Lady Gaue seems to be told of a future reduction in the gifts brought. In both cases I see the reserve of Christians about retaining the pagan offering. The old gods must, at least according to the words, now stand in low and ill repute. In the district about Hameln, the custom prevailed that if a reaper during binding passed over a sheaf or otherwise left something standing in the field, the others mockingly called out to him: "Shall Lady Gaue have that?" The widespread worship of the productive, nourishing earth also occasioned a variety of names among our forefathers, in the same way as the divine service of Gaia and her daughter Rhea mingled with that of Ceres and Cybele. The similarity between the cult of Nerthus and that of the Phrygian mother of the gods, Cybele, seems to me worth noting. Lucretius describes the peregrination of the magna deûm mater [great mother of the gods] in her lion-drawn car through the lands of the earth: Adorned with a turreted crown, the image of the divine mother is carried through wide lands with awe-inspiring effect ... When first borne in procession through great cities she silently enriches mortals with a wordless blessing; they strew all her path with brass and silver presenting her with bounteous alms, and scatter over her a snow-shower of roses, overshadowing the Mother and her retinue of attendants. (Lucretius, On the Nature of Things, 597-641)Ammianus Marcellinus, XXIII, 3: "There [at Callinicum in Mesopotamia], on the twenty-seventh of March, the day on which at Rome the annual procession in honor of the Mother of the Gods takes place, and the carriage in which her image is carried is washed, as it is said, in the waters of the Almo, he [Emperor Julian] celebrated the usual rites in the ancient fashion." Nerthus is likewise, after she has been driven around the land, bathed in the sacred lake on her wagon, and I find it recorded that the Indian Bhavani, Shiva's wife, is also driven around on her festival day and bathed by the Brahmans in a secret lake. Rügen or Fehmarn have been held to be the islands of the sea mentioned by Tacitus. In the middle of Rügen [an island in the Baltic sea] there is still a lake called the Black Lake or Burgsee (Herthasee) about which a legend circulates. In olden times the Devil was worshipped there, keeping a maiden in his service who, when he had grown tired of her, was drowned in the Black Lake. However bad the distortion, this will have sprung from the ritual reported by Tacitus, who says that when the goddess had finished her dealings with humans, she vanished in the lake together with her servants.

Jakob Grimm, Germanic Mythology, trans. Vivian Bird (Washington, DC: Scott-Townsend Publishers, 1997), 15-30. The title above is editorial. I have corrected errors in Bird's text, have restored some material from the original, and have provided translations of Latin and Old Norse quotations. Jakob Grimm's Deutsche Mythologie was first published in 1835, with many subsequent reprints and revisions. Bird's heavily abridged translation can be purchased from National Vanguard Books. |

|

|